Chapter 6

Remy’s house was a small affair. It dated back to the 70’s; a time when Malawi was still only a little way into its independence. The linoleum tiles, once the decor of the day, now wantonly displayed the polished concrete floors it covered. With handles placed at waist-level, the doors all closed with the muffled whisper, giving privacy to walls that had heard a thousand secrets.

Ailsa loved it immensely.

There was something about a house with history; house that had seen other families and been privy to the many triumphs and losses they had endured whilst under its walls. When she was younger, she could imagine herself finding a letter, or a secret room in one of these houses, and perhaps solving a mystery or two, like Nancy Drew, or the Famous Five. It seemed entirely possible, because these houses had character. They were unlike new houses, which were rather impersonal and had no secrets to divulge. These new houses waited, like a blank canvas, to be filled with memories and made interesting.

There were old memories in Remy’s house from families who had lived there before Remy’s mother had purchased the house in the 90s. But there were also memories from Ailsa’s childhood; weeks of school holidays spent running through its short corridors, around its squashed little rooms and out into the rather expansive yard.

These memories always greeted her as she stepped over the threshold and into the living room, and just for a moment she would smell the dry grass of the summers of her childhood, and be transported back to a time when everything was an adventure.

She stepped over the threshold now, but pushed the memories back in her mind. “Remy?” She called.

From the back of the house, where Remy’s room was, came her reply. “I’m coming! You could have waited in the car...”

Ailsa followed Remy’s voice. The bedroom door was ajar, and she pushed it open to reveal a mess. Although the bed was made (Remy’s mother was very particular about beds being made) clothes were spewing from the wardrobe, and littered the floor. One article of clothing had somehow found itself draped on one of the bedposts at the foot of the bed.

Unable to spot Remy, Ailsa cast her eyes over the room, wondering if perhaps, she had mistaken Remy for a pile of clothes. Remy emerged rather suddenly from beneath her bed, tugging on a black bra. Her hair was pulled back against her scalp in neat cornrows, making her head seem rather small.

“Geez Remy, you’re not even dressed yet!” Ailsa wailed, incredulously.

“I am, I am,” Remy said, waving Ailsa’s concerns off. “I already know what I’m wearing, Ails, I’m practically done. I just had to get this bra; I always kick it under the bed when I take it off. And then I forget!”

Ailsa shook her head. They would be even later to this week’s rehearsals. Ailsa moved over to Remy’s bed, and lay down.

“Don’t lie down, I told you I’m already done,” Remy scalded. But it was half-hearted. She extracted a pair of jeans and tugged them on, jumping as she tugged them higher over her hips.

Ailsa checked the time on her phone and decided it was better not to pay it any mind at all. She played some music instead, glad that she was just the means of transport and not the one the band was waiting for.

She thought of the last time she had sung with the band, and it made her think of Andrei.

How her hand felt in his...

She felt her stomach twist.

What had that been about? Surely, he had just held her hand for balance?

Each question was tailed by more question-marks than its predecessors.

She now went over the many times they had been together recently, scrutinising his actions under a new light. Was it possible, she wondered, that Andrei was... flirting with her?

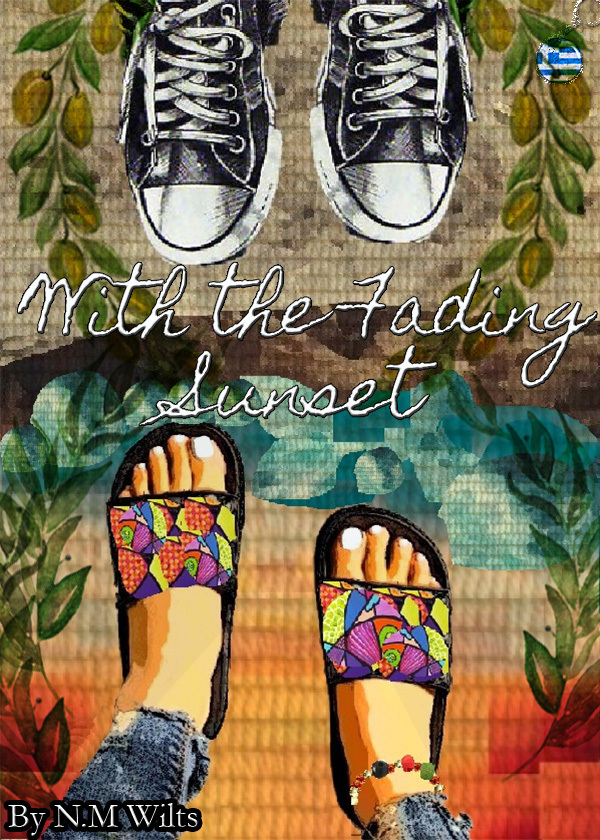

It was not that she thought herself beneath him, or that she thought herself above him. Ailsa saw how he could be attractive. He was smart and kind and funny, and his eyes, weren’t they blue like the Greek flag?

And she was - she was pretty. Perhaps a little pensive for some people’s liking, but other people liked this quality. She was a little stubborn, yes, and she liked to believe she had a good sense of humour, but to think of herself as an object of interest to Andrei now was strange and uncomfortable.

They were parallel lines.

If he was flirting, he must have thought her incredibly obtuse. But there was the possibility that he wasn’t flirting. Perhaps he was just really friendly? This sounded silly, even to her, but it was always really hard to tell with these kinds of things. You’d both say cryptic things and drop easily overlooked hints, perhaps a long look here and there and then eventually, someone would have to come right out and say it. Sometimes it paid off, and other times you came away disappointed. Ailsa had been through this before a few times.

“There should be a way to know if someone is flirting with you,” she said, to Remy. Remy, who was standing in front of her vanity putting on make-up mascara, put down her mascara wand. Her reflection smiled coyly at Ailsa’s reflection; a teasing eyebrow raised.

“Who’s flirting with you?” Remy asked, without turning around.

“Nobody,” Ailsa said, quickly. Remy’s eyebrows both rose in suspicion now, and Ailsa repeated herself slowly. “No one.” She swallowed. “I just mean, if people would just come out and say they were interested - in that way, or if there was some other way to know, life would be a lot easier.”

“Hmm.” Remy gave Ailsa a long look, before continuing with her make up. Ailsa felt her stomach twist again and was slightly annoyed. Wasn’t it enough that her very thoughts were being intruded upon by him? A physical response to the thought of him was quite the burden to bear. And all because of a simple act.

Hand-holding.

She wasn’t five years old.

“Well,” Remy said, “When you’re really confused about whether someone’s flirting with you, it helps to remember that TABTA thing. They Are But They Aren’t.”

Ailsa smiled, remembering a text post Remy had sent her once that gave this very advice.

Remy finished her make-up and found a shirt. Ailsa watched her brush her hair. She was back to wearing a familiar favourite of hers - a long wig that fell in layers, dyed auburn. Ailsa tried to remember the last time she had seen Remy’s hair and could not. Remy was the queen of wigs. As Remy herself put it, there was a wig for every mood.

Satisfied with herself, Remy busied herself with picking up errant hairs that had fallen to the dresser and the floor. Ailsa stared at one of the walls, painted an off-white since time immemorial.

“Aunt Vi was quite superstitious, wasn’t she?” Remy mused, out of the blue. It seemed that while Ailsa had been lost in her thoughts, Remy had been consumed by her own. Ailsa looked away from the wall and at Remy, who was straightening up after tossing something in the bin.

“I suppose,” Ailsa said mildly.

“She warned me once to make sure I always flushed any hairs that fell out down the toilet,”

“Oh yes, she told me that too,”

“She said someone could use it to cast a spell on you or something.”

Ailsa thought for a moment.

When she was younger and couldn’t sleep, Ailsa would sit by the window and stare out at the night sky. She had never been interested in astronomy, so she did not know the names of constellations, nor the stories behind them. But, even for this African child, the night sky was a wonder to behold. Unpolluted by the lights of skyscrapers, and stretching out overhead as far as the eye could see and the mind could imagine, were millions of stars. The night sky was a magic thing to behold, a mystery to comprehend... one could only guess at what sort of ideas it inspired in the mind of an imaginative child like Ailsa. It was a habit that Ailsa had kept, until one fateful conversation with her aunt, when she was eight years old.

“Never look out the window at night,” her aunt had warned her. “You don’t know what could be looking back.”

Ailsa’s parents were rather no-nonsense people, and had discouraged all ideas of ghosts and goblins, monsters and things that went bump in the night. It had never occurred to Ailsa therefore that someone or something could be out there, hidden by the night, but staring back at her. The thought had made her shiver, and she had moved her bed away from the window afterwards, so as not to be tempted to find out what exactly could be looking back at her.

She could not remember what her aunt had been talking about and why her aunt had thought it necessary to make such a pronouncement, but now that Violet was no longer here, Ailsa treasured these snippets of wisdom, holding them close to her heart for moments in the future when they would come in handy. Even if they were rather puzzling. They contrasted rather noticeably with her aunt’s devout faith.

“She really believed that stuff, didn’t she?” Ailsa said. The way her aunt had looked when saying these things... it was almost as though she was afraid.

“Yeah. Remember how she’d always tell us to burn our used pads?”

Ailsa had forgotten this, but at Remy’s prompting, it came back to her. She sat up.

Make sure you burn them Ailsa. Someone could use those...

But Ailsa had simply thrown her sanitary pads in with the rest of the waste from the house. It was all carted off by the waste management truck that passed through their neighbourhood every week. Who would sift through all that rubbish, she wondered, looking for a single pad from a girl like Ailsa? She had no enemies, and neither did her parents. It was a strange superstition indeed. Aware of her mother’s practical ways, Ailsa had never consulted her on the matter.

“I guess it was just one of those things,” Ailsa surmised. She turned her empty palms up to the ceiling and shrugged.

“I think it was something to do with that friend of hers though,” Remy said. Almost as an afterthought, she added, “That light lady with the big beauty spot.”

Ailsa stilled.

“What?”

“Vi had that friend - I don’t know if you’d remember Ailsa, maybe you were young,” Remy seemed to talk in circles, using a lot of words without really saying anything at all. Ailsa waited. “It was a long time ago,” Remy continued. “Vi had a friend. She was really perfume-y smelling. They used to do just about everything together. And then... I think they had a falling out? I don’t know. She just wasn’t around anymore. It was a long time ago. I can’t even remember her name.”

Ailsa’s mind was racing. What were the odds that the woman Remy was describing was the same woman that Ailsa had been dreaming about? The one she felt she knew? It would be an extraordinary coincidence, but also, didn’t they say your brain always used faces you had seen in real life to make the faces in your dreams? This meant that the woman from her dreams was not invented. Her face had come from Ailsa’s memory.

“Are there any pictures?” Ailsa asked, carefully, thinking of Remy’s mum’s old Polaroid camera. “Do you have any?”

“Probably...” Remy said. She was busy finding some shoes now. “I’m sure your parents should have some too, somewhere.”

“Yeah,” Ailsa said. She tried to make her voice sound light. For some reason, she was reluctant to tell Remy about the dream. “But- but why would the superstition be the friend’s fault?” Ailsa pressed.

“Oh, I don’t know. I just got that vibe. Something my mum said once, I think.”

Ailsa was about to ask what exactly Remy’s mother had said, when Remy picked up her phone and cursed loudly.

They were extremely late.

Once they were in the car and on their way, Ailsa turned to Remy once again.

“What did your mum say?” Ailsa asked.

Remy muttered something under her breath and tore her eyes away from the small train of cars in front of them. There up ahead, a rusting heap of a truck had broken down, and was taking up one side of the main road. She looked at Ailsa as though she had just realised Ailsa was in the car too. “Huh?”

“What did your mum say about Aunt Vi’s friend?” Ailsa paused.

“Oh, yeah, I think she was into some weird stuff Ails-” Remy’s phone began to vibrate in her lap. Another expletive was used, and Remy turned down the stereo as though she was about to answer the call. “Man. I’m really late... I think it’s better I don’t get this.” She put her fingers up to her lip, which she was nibbling on anxiously. Her leg was tense, as though stepping on an imagined accelerator pedal. It was as though she had turned down the volume so she could direct all her attention to being worried.

“Weird stuff like what?” Ailsa pressed.

“Eish!” Remy exclaimed. Ailsa wasn’t sure if this expression was directed at her or at the slow-moving line of cars in front of them. “Weird stuff, Ailsa. Like... traditional medicines and that kind of stuff, you know?”

“What?”

“WITCHCRAFT, Ailsa. Ufiti.” Remy resulted to the traditional word in all its ugly and twisted glory.

“I know, I heard you. I meant ‘what’ like ‘what?’ Not ‘what’ like ‘what?’.”

They were finally moving. It was a slow creep forward, but it was progress all the same. Ailsa was relieved. There had been a beggar up ahead, a man with a single crippled arm, moving slowly from car window to car window, begging for alms. Ailsa’s purse was next to empty, and she always felt bad when she had to tell these people she had nothing. She imagined it sounded like a lie to the beggar; she - a well-dressed, well fed girl in a shiny little Nissan March - had nothing to give.

“That’s why she fell out with aunt Vi?” Ailsa asked. “Witchcraft-ey stuff?”

“Yeah, I think so... Maybe you should ask your mum about all this.”

Ailsa shrugged. What would there be to ask about? She had the essence of the story. They came to a stop again. The beggar was two cars away. The occupants seemed to be turning him away.

It could be that they too, had nothing. On the other hand, Ailsa had heard some strange stories about beggars. Aunt Vi once claimed to know a woman, who knew a woman, who had heard it first-hand that some people begging for alms were only looking to hurt you.

Some of them carried sharp knives, and when you rolled down the window - well, that’s when they got you. Hadn’t a woman in America been killed by someone begging for alms? The American woman had rolled down the window to give them some loose change and been stabbed to death. A senseless killing, for someone who had simply intended an act of kindness.

“It is better to be safe than sorry, Ailsa,” Aunt Vi had said. “To be forewarned is to be foretold.”

- Of course, this was in America. They were not in America. Ailsa too had raised this point. The warning had taken an ominous turn.

Some of these beggars, Aunt Vi said, would carefully select a car. This car would go... that car would go... When just the right person came along, they would approach. They paid attention to who they chose, you see, and the occupant would always roll down the window...

“That’s when they induct them into the satanic church!” Aunt Vi had said.

This rather abrupt escalation had prompted Ailsa to laugh incredulously. It was unclear who was inducted into the church - the beggar or the person in the car, and how exactly this would happen in traffic. Despite prompting, Aunt Vi had pursed her lips and refused to speak any further on the matter.

“Just be careful with these street kids and these street people.” Aunt Vi had concluded. She had looked about them as though she expected one to jump out from underneath the sofa Ailsa was lounging on at the time.

Ailsa simply chuckled and shook her head, dismissing the tales in their entirety. In her opinion, Aunt Vi spent too much time reading conspiracy theories and the fear-mongering fictions that populated her WhatsApp groups.

Of course, it was easy to laugh at topics like that in the daytime, under the illumination of that warm Malawian sun. But when the night fell, and shadows loomed...

Ailsa shivered.

To think that Aunt Vi had had a friend involved with those sorts of things...

“Well, no wonder Aunt Vi broke the friendship off,” Ailsa said. “Aunt Vi hated all that kind of stuff.”

“Ailsa,” Remy said, cautiously, as they eased around the truck “It was Aunt Vi who was involved with those kinds of things. Not her friend.”

*

For lack of a better word, Ailsa was perplexed.

Waking up in the morning two days later, Ailsa lay still for a few minutes thinking about the dream she had been having just before she woke.

She had dreamt that she was going shopping with her mother, but Ailsa could only move if her mother told her to. She couldn’t move or speak otherwise. At some point, Ailsa had been surprised to find that she was only dressed in her underwear. Her mother had then begun to snap at her, urging her to hurry up because the people in the shopping mall could see in through the long windows of the small shop they were currently in. For some reason, the shop had been painted a shocking shade of pink and adorned with zebra-patterned drapes and pink glittery lace. Ailsa didn’t know why this detail had particularly stood out to her, but it had.

People started looking in through the windows, and Ailsa had tried to sew faster - suddenly, she was sewing - but then her teeth had started falling out, so she had to keep her jaw clenched tightly and her lips pressed together to keep her teeth from spilling out onto the floor.

Towards the end, the dream had become less frantic and strange; Ailsa’s mother ripped one of the zebra-patterned drapes from the wall and wrapped it around Ailsa. Her father had appeared to push the shopping trolley, because her mother wanted to sleep in its basket; which was somehow large enough to accommodate her.

It was a ludicrous, over the top dream, and it provided some respite from the two main topics on Ailsa’s mind, Andrei and Aunt Vi.

She hadn’t spoken to Andrei since they had parted ways on Monday morning. Having gone over it again in her mind, she had concluded that he was not flirting with her. He had simply held her hand because it was the sort of thing one might be prompted to do when they experienced something beautiful and peaceful early in the morning. You’d feel inclined to reach out to whomever was next to you, and squeeze their hand, Ailsa mused, as if to ask if they saw or felt whatever you saw or felt too.

And perhaps she had looked slightly unsteady on her feet, wading out into the pond. She had held out her hand to stabilize herself. In taking it, Andrei was only being helpful. Ailsa felt that to start misinterpreting his actions now, would lead to a rather embarrassing conclusion. And so, she had done her best to put him out of her mind.

On the other hand, she was confused about her Aunt. Something about the whole matter felt rather off. She had looked through an old photo album of her mother’s when she had returned home on Monday. While she had a good time reminiscing, the woman from Ailsa’s dreams had not appeared in any of the photos.

The peculiar thing was, when she had asked her mother about Aunt Vi having such a friend, her mother had paused for a moment, as if considering her response, only to say she didn’t know who Ailsa was talking about.

Remy had promised to look for a photo, but Ailsa felt she couldn’t put much stock in this notion, because Remy could be forgetful. She could’ve gotten up to look there and then; they had been watching a movie on Tuesday afternoon when Remy had made this promise. But she hadn’t and Ailsa, still feeling that she could not say anything about the dreams, had said nothing.

It scared her a little, to think that she could be dreaming of someone who had something to do with whatever it was that had made aunt Vi superstitious.

Ailsa sighed, turning instead to the mirror that hung on the wall opposite her bed. Sometimes, in the middle of the night, she would get a sudden fear that she’d wake up to find her reflection sitting up and staring at her.

A snippet of a conversation with her aunt came back to her. “They use mirrors,” her Aunt had said. “When they’re getting revenge on someone or casting a spell, they use mirrors. They say your name into a mirror and you appear before their eyes. All they have to do is prick your image with a needle...”

Ailsa looked at her mirror feeling a little like she was a character on a mockumentary show and the mirror was the camera. Her tousled, oily-faced reflection gave her the same look. There I am lying on my suitcase-elephant, she thought. Still, a part of her was relieved.

She didn’t want to think about her aunt that way. This was not a case of white magic and dark magic. If you were into the occult in Malawi, it was more likely than not that you were into the bad stuff. Remy had specifically used the word ufiti.

Perhaps Witchdoctors were a grey area, but Ailsa had yet to hear anything good associated with that word. Every Malawian child knew what aMfiti did. They transformed into creatures that flew in the night and ate dead bodies in the graveyard. -Perhaps this was an urban legend; a tale meant to scare little children into behaving. But even amongst adults, if a person was rumoured to practice witchcraft; unexplained deaths of close family members or rivals, accusations of murder and mysterious sicknesses usually followed in their wake. It was not some poor misunderstood soul walking around with the weight of the world on their shoulders. It was a person enveloped in an ominous negative energy. One look and you could see why people would think it of them.

Remy had tried to reassure Ailsa as she got out of the car.

“It was a long time ago Ailsa. I don’t know if my mum is sure about how true this is. And anyway, people change constantly, you can never fully know someone,” she’d said.

But to think of Aunt Vi in this way was making Ailsa’s stomach turn, even if it had been once upon a time. She didn’t know if it was the ufiti itself or the fact that this part of her Aunt was unknown to her - something so major, but she felt uneasy about it all.

She felt that there was more to the story. One could not just be accused of witchcraft. Something always happened to prompt such an accusation in the first place. The fact that Ailsa was having dreams about it only served to heighten her fears.

What had Aunt Vi done?